We interviewed 590 women in Brazil

The goal was to understand more about their mobility and safety patterns

We ended up discovering a lot more

I feel that my independence to move around is hampered by insecurity in public spaces in my city

I avoid standing alone in a public place, I only use public spaces to move around

The safety of a space is the most determining factor in my mobility decisions

I feel that I care more about ways of getting around than the men in my family or male friends

Deployment of self-protection tactics as mechanisms of urban resistance on female mobility decisions

Studying the construction of cities is also comprehending struggles and resistance in the occupation of spaces. The city is a mirror of the current social dynamics and, at the same time, it is a textured canvas that influences social dynamics of control and domination between people.

The city is the territory of power disputes.

The construction of our cities fundamentally revolves around the idea of private property – private property dictates many of our behaviors and the way each of us relates to the city. But how so? Well, the concept opens up to several paths. Private property (or the idea that “what’s mine only belongs to me and nobody else has any claim to it”) by itself already creates a huge barrier between what is or is not ‘public’ and collective. What happens in private belongs to me, but what happens in public not so much… Many authors have already exhaustively pored over these concepts, but what is important for us here and now is to understand that this concept of what is private and of what is public has a direct influence on what we call…

The sexual division of labour is a very old and socially imposed idea that each human being has a function as a worker, depending on their sex and ‘gender roles’. It is up to men to do ‘productive’ work – that effort known as ‘work’ in fact, which in the capitalist model is transformed into money based on productive effort. Women are responsible for ‘reproductive’ work, the one linked to care, reproduction and affection and, for the most part, unpaid. The sexual division of labour dictates the question “What is your social function as a man or a woman?”.

The ‘sexual division of labour’ goes hand in hand with the ‘sexual division of space‘. Men are responsible for public spaces and collective decisions. Women are in charge of private spaces, houses. According to the sexual division of labour, women are not entitled to any type of public space – they do not belong to them, they should not be accessed and they are not responsible for any decision.

Although nowadays, theoretically, we women can access public spaces freely, in practice we know that this is not the case. Even when we ‘could’ be somewhere, it is often not the most inviting place for us. We are afraid, a fear based on our own experiences and the experiences of those close to us (mothers, grandmothers, sisters, cousins, friends). Many times these fears are even almost abstract fears, passed on to us by the news we see every day and by the terror messages we receive that maybe these spaces are not safe at all for anyone, but especially for us.

This page is part of a comprehensive research, compiled for you in a more accessible and democratic way of reading

To access the complete document of this study (in Portuguese), click on the button below

These structures of domination and control of spaces and people serve small groups that benefit too much from the ‘division’ between oppressed groups. These power structures created on top of a single model of living and occupying space also created a dynamic of silence and invisibility of anyone who does not fit the model. Public and decision-making spaces truly belonged only to this small group and excluded the others – who continue to make use of these spaces, but almost exclusively for circulation and not for actual leisure/being.

The creation of an urban model in which collective meeting spaces are destroyed by fear is also part of a domination strategy in which these oppressed groups do not feel comfortable actually meeting and discussing their problems. In the case of women, as each woman is inside houses, locked and afraid, going from private place to private place, controlled, it becomes more difficult for them to talk, discuss solutions to their problems and oppressions and not feel alone in your fears. For working women, who use public spaces for work, the city becomes exclusively a circulation space, used exhaustively but never for anything that is focused on belonging, leisure, choice and being.

If there are a lot of women walking in the same place I feel safer. It seems that everyone is in the same boat, it seems that everyone is united and we can help each other, we feel more welcomed

21 years old, cis woman, white, heterosexual, non-PwD, no children, incomplete higher education, Student, average family income of 4 to 10 MWs, individual car as the main mode of transport, takes 25 minutes to reach the city-center from her residence

A place is always a place for someone. It is linked to the affections and fears that this space brings to each person. A place built under a “neutral” planning perspective will be a place of potential comfort for men, as it was designed by and for them, while it can often be a “non-place” of great insecurity for a woman who passes by.

“Consequently, out of necessity or desire to occupy public spaces, many women ended up creating mechanisms and tactics for the “safe occupation” of public spaces, seeking to develop mental safety maps based on their own experiences and those of others. These mental maps are often seen as a “natural” female ability, when in fact they are social impositions that make women responsible for maintaining their safety.“

These tactics and mechanisms for negotiating the use of spaces become a naturalized daily effort of all women, and which at certain times even generates increased travel costs and loss of opportunities for work, study and leisure, in addition to normalizing stress and anxiety about the city.

“I HAVE PLEASURE IN WALKING IN THE CITY, BUT IT REQUIRES ME TO EMPLOY SOME INSTRUMENTS”

To arrive at the results of this study, we interviewed and collected data and perceptions of women who live different realities in Curitiba (Brazil). We had a time limitation to carry out the survey, so we had to delimit a space. Perhaps these results would be different in different cities – and we take the opportunity here to invite more people to conduct the same study in their cities, it would be really cool to be able to compare realities too.

The intention of this research is to contribute to the scenario of what we call “feminist urbanism” and to present you with new information about the relationship that women have with public spaces and the tactics we use to move around.

Our hypothesis at the beginning of this study was that the concern for safety is a very relevant factor when women make their mobility decisions, and that these insecurities generate limitations in urban freedom. If you’re a woman, maybe this hypothesis seems kind of obvious to you, right? But we needed to prove it! As expected, the hypothesis was confirmed by the study. Based on that, we would also like to point out relevant data collected and related analysis, so that we can think of new paths and perspectives for building cities that are in fact more inclusive.

Take a look below at the data we found!

A women's age influences her relationship with the city. Whether or not she has children, too.

- While collecting testimonies and through the data analysis, we observed that women aged 35 or over and with children tend to be more indifferent in regard of their own safety in public spaces, when compared to younger women without children. These women who are most indifferent to their own safety, however, are very afraid of something that might happen to their daughters and younger women.

When you become a mother you can no longer think as a single person. The paths (...) that I would use before, I don't use them anymore. Places where the possibility of danger was just a possibility, you treat it as a certainty. You won't play with the chances.

37 years old, cis woman, white, heterosexual, non-PwD, with children, postgraduate, UX researcher, average family income of 10 to 20 MWs, individual car as the main mode of transport, takes 15 minutes to reach the city center from her residence

_ We observed that women tend to always perceive themselves relative to someone – someone’s mother, someone’s daughter, someone’s sister or girlfriend. Never single and totally independent individual. This perception also indicates the need to create self-protection networks in the public space.

_ Younger women without children have a perception of greater concern for their safety than older women with children. They also prefer to ask other women for help in cases of harassment and violence, while older women with children do not observe this influence of the presence of the protection network as much.

Without children

No Data Found

With children

No Data Found

(Interactive graphics - move the arrow above them to see values)

Without children

No Data Found

With children

No Data Found

(Interactive graphics - move the arrow above them to see values)

_ This difference in the perception of safety depending on age and motherhood is also repeated when we analyzed the types of safety tactics these women use in public spaces.

_ See in the graphs below how the tactics of changing clothes before leaving home, sharing location in apps and having objects at hand that can be used as defense tools are much more present in the daily lives of younger women without children:

Without children

No Data Found

With children

No Data Found

(Interactive graphics - move the arrow above them to see values)

Without children

No Data Found

With children

No Data Found

(Interactive graphics - move the arrow above them to see values)

I remember when I was about 16 years old, I was coming home from school alone and I was verbally harassed from the school door until I got home. I got to my grandma's house and I told her 'grandmother, how absurd! They were harassing me through the whole path', and then my grandma said: 'Oh dear, the prettier you are, the more men tease you on the street, so be happy, it's a sign that you're still up to date, look at your grandma...'

21 years old, cis woman, white, heterosexual, non-PwD, no children, incomplete higher education, Student, average family income of 4 to 10 MWs, private car as the main mode of transport, takes 25 minutes to reach the city center from her residence

_ For women with children, there is a feeling of not belonging anywhere, and never being able to access public space easily.

_ There is also a collective unconscious reinforcement that older women have already lost their social value, as they fulfill the role established for them as mothers.

_ Such self-perception, of having less reproductive value and supposedly less exposure to violence, may also be related to the perceptions of older women who already have children that it is not necessary to use some self-protection tactics with themselves, but always reinforcing such tactics to their female daughters.

_ On the other hand, young women feel that there is a certain collective acceptance of the violence that will be committed against them.

The simple right to exist starts to be questioned: the simple act of moving around without justification or leaving private spaces becomes an attitude seen as one of irresponsibility, and all strategies of absence become gears made to undermine individualities of each woman

“It’s not safe for anyone”: more vulnerable black and LBTQIA+ women

For women in the LBTQIA+ community, insecurity is even clearer. The use of tools that can be used for defense is important for the total group of women, but even more relevant for women of non-hetero sexual orientation. For the LBTQIA+ population interviewed in the research, the presence of security forces (private and state) generates more fear than security.

[I make an effort to] not show affection on public transport or in public spaces for fear of lesbophobic violence

32 years old, cis woman, brown, lesbian, not PwD, no children, graduate, lawyer, income family average of 4 to 10 MWs, individual car as the main modal, it takes 15 minutes to reach the city center from her residence

Heterosexuals

No Data Found

LBTQIA+

No Data Found

(Interactive graphics - move the arrow above them to see values)

Heterosexuals

No Data Found

LBTQIA+

No Data Found

(Interactive graphics - move the arrow above them to see values)

In racial terms, the impact of gender violence is even greater for black and brown women. Many times the fear of racial violence proves to be even greater than the fear of gender violence, and this fear can even be financed by the very powers of the State – this issue is even more pronounced in the analysis of class and territory, analyzed shortly. There is a greater sense of network and community dependency for black and brown women, and also greater awareness of the importance of their own presence for other women to feel safe as well.

White and Asian

No Data Found

Black, Brown and Indigenous

No Data Found

(Interactive graphics - move the arrow above them to see values)

White and Asian

No Data Found

Black, Brown and Indigenous

No Data Found

(Interactive graphics - move the arrow above them to see values)

We also realized, throughout the interviews for this research, that there are opposite poles of analysis on the relationships between white women and black/brown women occupying the same spaces.

White participants who throughout the interview demonstrated greater awareness of racial issues pointed out that they know they have more responsibility in using their privileges to protect other women – including in relation to ostensibly unfair claims by security powers.

For the black and brown women interviewed there are two points: some report that the presence of white colleagues/friends/wives changes their relationship with the city, generating greater security. However, this interracial relationship can also be more complicated and violent, especially when it comes to issues of class and territory. “Some black and brown participants pointed out that they had already suffered violence from white women, and that the confidence to ask for help in case of need depends on many factors.”

There is no such thing as freedom... I'm too afraid to get in my car and leave alone because I'm afraid the police will stop me and say 'dude, that's not your car', or not even let me say anything, just open the door and start shooting... A black woman with dreadlocks... until I explain anything, God knows what can happen, so I try very hard to take precautions

43 years old, cis woman, black, lesbian, not PwD, no children, higher education, photojournalist, average family income 2 to 4 MWs, individual car as the main mode of transportation, takes 30 minutes to reach the city center from her residence

"This built image ["of the black bandit"] that makes white people afraid of us. Then people end up really afraid, 'ah, this place here, they told me it's a dangerous place' and then you look around most people are black and poor…”

43 years old, cis woman, black, lesbian, not PwD, no children, higher education, photojournalist, average family income 2 to 4 MWs, individual car as the main mode of transportation, takes 30 minutes to reach the city center from her residence

“We are at risk just for existing”: the influence of income, territory and schooling

Throughout the research, we also noticed a big difference in the perception of public safety depending on this woman’s income, education and location in the city – whether she lives in the periphery or in the center, for example.

The information that called our attention the most in this regard was the renunciation of women from the periphery and those with lower incomes to occupy public spaces. When asked “I already gave up on a work/study proposal because I would have to go back alone at night”, women with lower income and who live more than 30 minutes from the city center agree more with the statement, when compared to women with higher income and who live close to the center (take a look at the graphs below).

<30 minutes of travel downtown - residence

No Data Found

Average family income of up to 4 MWss

No Data Found

>30 minutes of travel downtown - residence

No Data Found

Average family income of more than 4 MWs

No Data Found

(Interactive graphics - move the arrow above them to see values)

These data point to some worrying realities: mobility unsafety helps to keep low-income and peripheral women in the place they already are and prevents upward social mobility.

Women who already have a higher income and who live closer to the center, despite also admitting to feeling a certain fear, are not as inclined to refuse work and study proposals because of the security factor.

This disparity goes even further when we analyze beyond work and study and observe the relationship between women and leisure spaces. Peripheral and lower-income women agree more with the statement “I already gave up going to a leisure event because I felt insecure about commuting” than higher-income women who live close to the center.

This issue is especially problematic as this type of limitation tends to confine even more peripheral and low-income women to their own homes and communities, distancing them from other urban infrastructures.

<30 minutes of travel downtown - residence

No Data Found

Average family income of up to 4 MWs

No Data Found

>30 minutes of travel downtown - residence

No Data Found

Average family income of more than 4 MWs

No Data Found

(Interactive graphics - move the arrow above them to see values)

The testimonies of the participants point out that they have almost no fear of moving within their communities, but that this fear arises or increases a lot when they have to leave them and ‘go to the rest of the city’.

Participants who live in communities/favelas or who have direct links with them also point out that they do not agree with the “collective understanding” about insecurity in communities.

“I have never been robbed [emphasis] within the community and I don't know anyone who has been robbed within the community. But the police have already invaded my house, already broke some things there, pointed their gun to my head, to my husband's head. In the surroundings, however, which are middle-class neighborhoods, I'm afraid to walk. (...) My daughters always went to the ice cream shop, bakery, market, wherever they wanted to go alone, at whatever time they wanted, walking through the streets of the community [when we lived there]. Now [that we moved from the community], that they have to go in and out to take the same classes [that they did before], I'm like "okay, let's find a way to take this child there" [because they can't 'cross borders alone']”

43 years old, cis woman, black, straight, no PwD, with children, complete higher education, businesswoman, average family income of 10 to 20 MWs, car as main modal, takes 5 minutes to reach the city center from her residence

Do your mobility choices influence your perception of safety? Yes!

We know from the theoretical foundation of this study that public spaces and streets were always presenting themselves to women as places for dislocation, never for pauses. As a result, mobility has a direct impact on women’s daily lives.

I spend more than I would like (or needed) on transportation due to security reasons

Many participants point to cars as the means of transportation in which they feel safer due to the greater speed and greater isolation it provides. They prefer (whenever they can) the additional expense and isolation of the urban environment to the constant fear they feel in other means.

“Whenever I can, I prefer to take a car (whether private or app), because I feel safer”

(Interactive graphics - move the arrow above them to see values)

No Data Found

At night, I don't feel safe not even in a car... I'm always on the phone, either with my mother, or boyfriend, or friend, because if something happens I'm on speakerphone and I give a shout and someone knows that something happened...

26 years old, cis woman, white, heterosexual, non PwD, no children, complete higher education, Engineer, average family income 10 to 20 MWs, individual car as the main mode, it takes 8 minutes to reach the city center from her residence

We also tried to understand the influence of car use in comparison to public transport, in particular the use of mobility-apps versus public transportation. Most participants indicate that they disagree with feeling safer on public transport than on app transport, but…

When observing women who live more than 30 minutes away from the center, the discrepancy in disagreeing decreases a lot.

<30 minutes of travel downtown - residence

No Data Found

>30 minutes of travel downtown - residence

No Data Found

(Interactive graphics - move the arrow above them to see values)

These differences can be explained by the differences in perceptions exposed by the participants. Some say they never take mobility-apps due to the insecurity of being alone with an unknown driver (when it is a male driver).

“Most reports of people giving up using mobility-apps are related to the experiences of harassment lived by the participants themselves or by third parties. Some report using security tactics when using the apps, such as sending their location or pretending to talk on the phone.

Some participants claim that commuting using mobility-apps would be safer than public transport due to the lack of punctuality of the buses (requiring them to spend more time alone at bus stops) and also due to the excessive proximity to many unknown people.

When I used public transportation, if it was during the day, my perception of safety was very similar to when I choose to walk. But at night... when I had to travel for 30 minutes and the bus was empty, I was very afraid, and I would sit behind the driver and be frozen with fear of anyone getting close. So at times public transport felt more dangerous than being on foot.

26 years old, cis woman, white, heterosexual, non PwD, no children, complete higher education, Engineer, average family income 10 to 20 MWs, individual car as the main mode, it takes 8 minutes to reach the city center from her residence

Even at night I feel safer on public transport… I don't know, I think that if something happens, there's at least one person who will somehow try to help me. If I'm walking and feeling in danger, I always look for a bus stop, a station, something that will make me feel a little safer or it will have better lighting.

21 years old, cis woman, white, heterosexual, non PwD, no children, higher education incomplete, Student, average family income of 4 to 10 SMs, individual car as main modal, it takes 20 minutes to reach to the city center from her residence

Some participants presented some discomfort when realizing that the wave of precariousness of public transport, however, does not guarantee quality private transportation. The participants also pointed out that they feel afraid in private transport due to fear of harassment and but also for violence in traffic.

With regard to commuting times, there is a greater difference in perception between day and night among cyclists and pedestrians than among car drivers.

"I really wanted to go by bike on a hot night… but I haven't done anything by bike at night for years because of fear. I don't have the courage, I can't. Several fears involved. I would do everything by bicycle if I could… but then I keep studying which route I have to take, especially if it’s a place I’ve never been, or it’s a place where I have to think about the route because of safety… So sometimes the journey, I don't know, is only 5km long, it's very close, then I think 'why I'm going by car? it's very close!', but then when I think about safety… and I give up the bike."

43 years old, cis woman, white, heterosexual, non PwD, no children, postgraduate, teacher, average family income from 4 to 10 SMs, bicycle as the main mode of transport, takes 20 minutes to reach the city center from her residence

Female cyclists are also more aware of the importance of their presence for other women.

The greater relationship with the public space and a greater community feeling among bicycle users, in a “community of cyclists”, are perhaps possible explanations for this greater “urban sorority”. The mechanisms which cyclists resort to, who have to face not only gender fears, but also fears linked to the lack of infrastructure and traffic violence, can also be encouraging factors for this behavior and such a deeper awareness about the individual role in building a safer collective space.

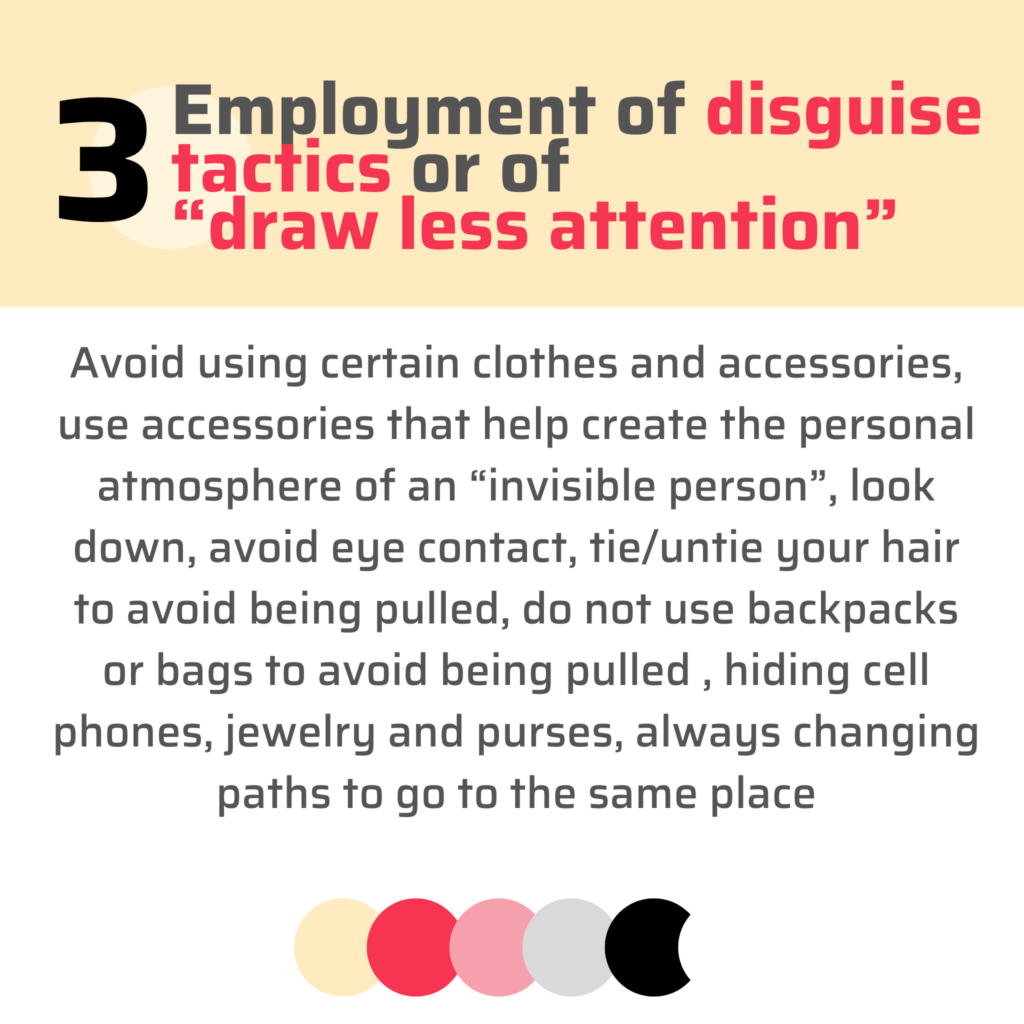

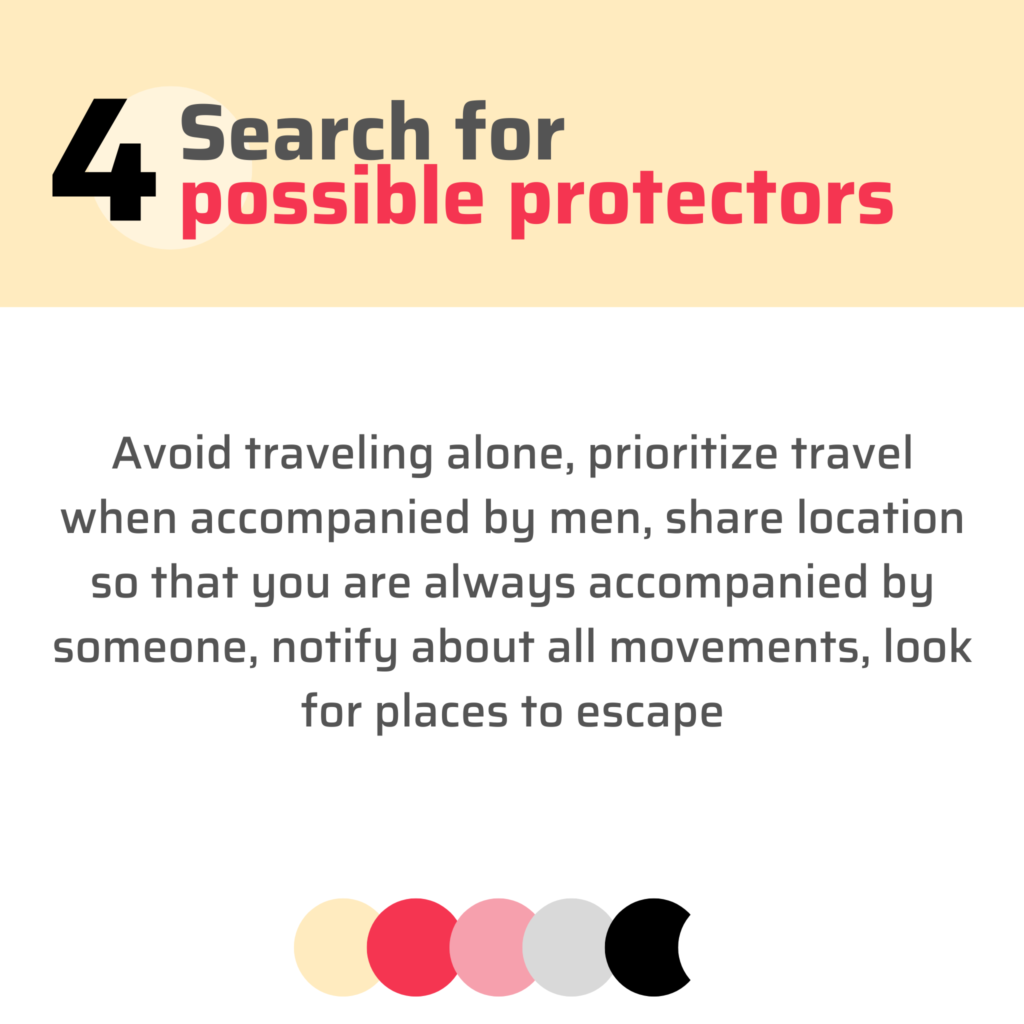

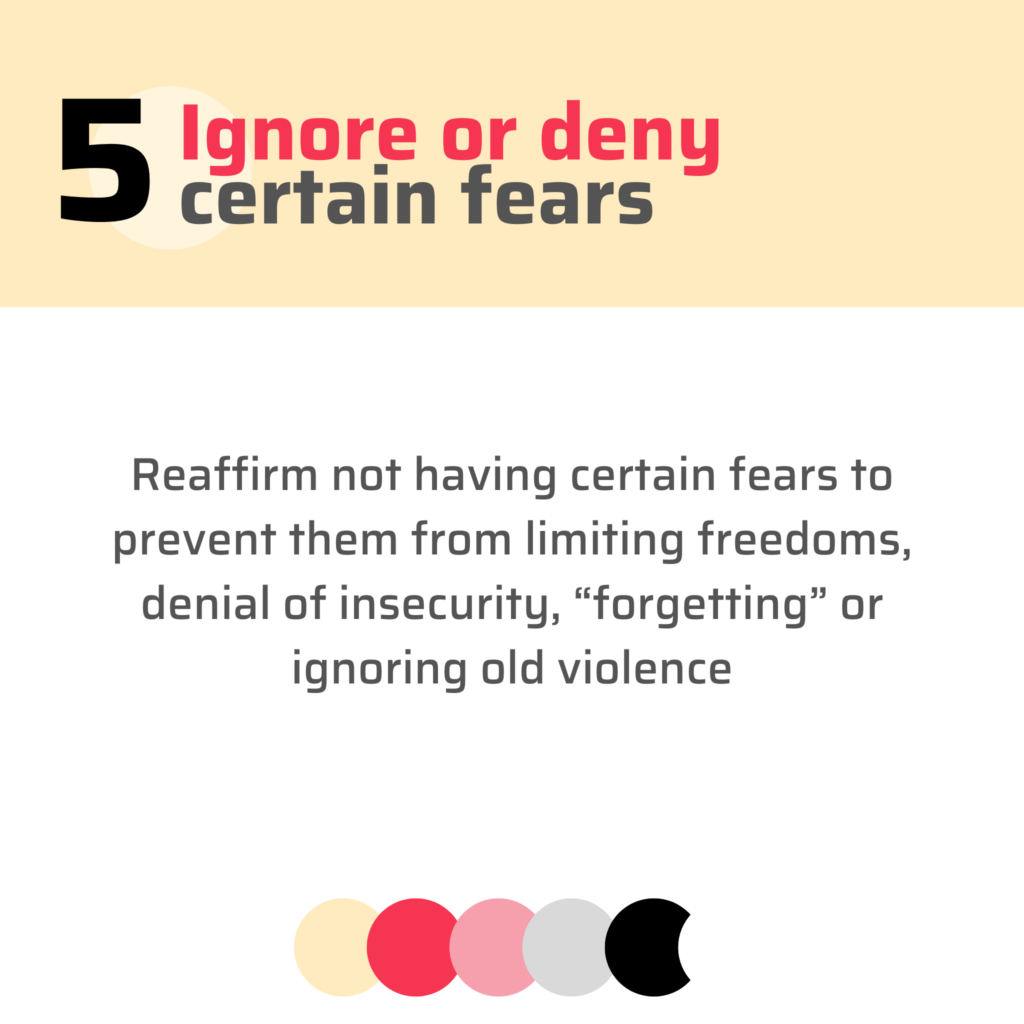

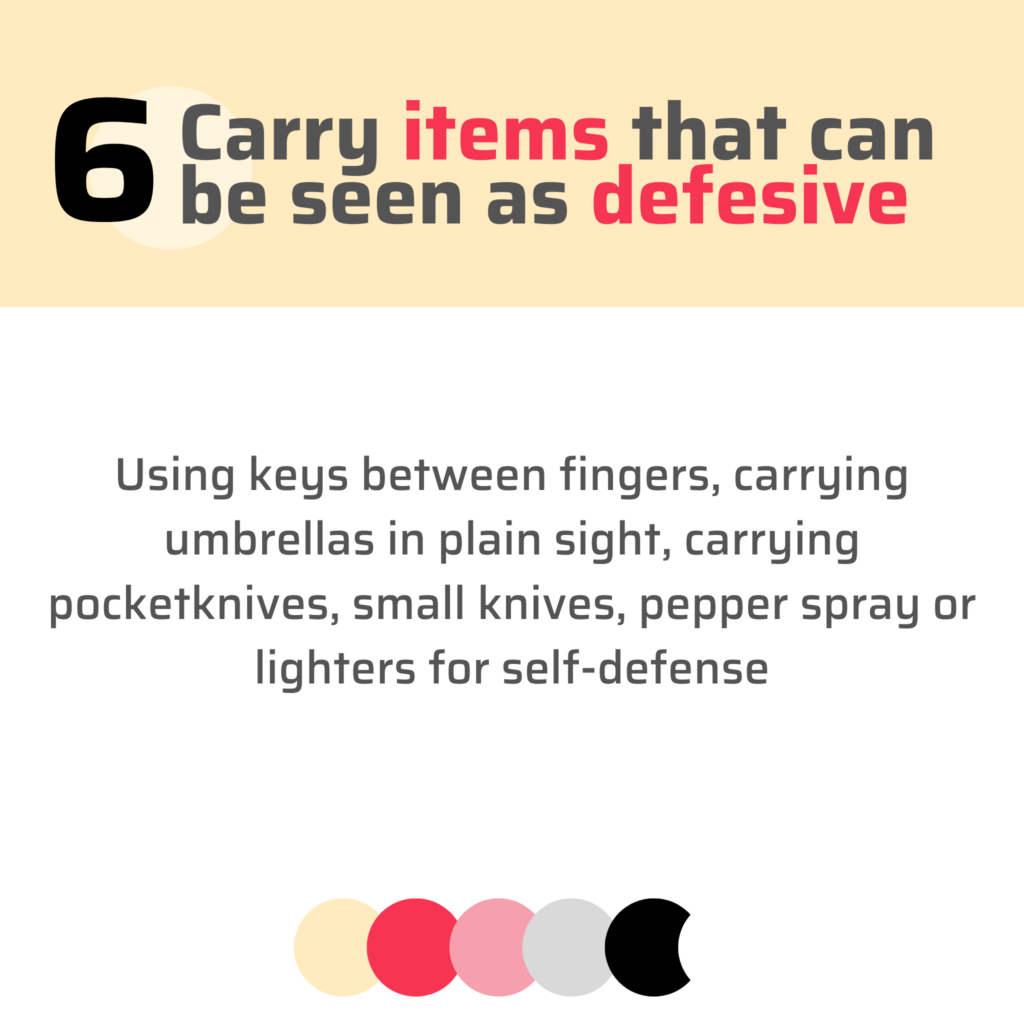

“Do you have to do all this to leave the house?” : Self-protection tactics

Throughout this research, we established 7 groups of self-protection tactics used by women and reported by research participants. Below, you can understand a little better each one of them, their impacts and ways of execution. Those are not recommendations, but a sum up of strategies already employed by women while using public spaces.

"For me it's automatic now… We're all kinda neurotic"

"Every time it was something mandatory I did it… but if it's something more related to leisure, I couldn't think of any time I thought 'it's dangerous but I'm going', because when it's up to others I manage and do it , but when it's about me I'm already more reticent, so I probably wouldn't do it"

26 years old, cis woman, white, heterosexual, non-PwD, no children, complete higher education, Engineer, average family income of 10 to 20 MWs, individual car as the main mode of transport, takes 8 minutes to reach the city center from her residence

“I have to activate all my senses, I try to be more awake, to be alert”

41 years old, cis woman, brown, heterosexual, non-PwD, with children, postgraduate, businesswoman, average family income of 4 to 10 minimum wages, bicycle as the main mode of transport, takes 20 minutes to get to thecity center from her residence

“If I have a different watch, if I have something different on me, I take it off… I do it more to avoid attracting attention in any way, other than having a real fear of being robbed, I think it's having one less thing to call attention to. I plan when I'm going to go out… if I'm just going to take the bus or I'm just going to walk, I'm going to go out wearing one kind of outfit… if I'm going to take a car or take an uber, another kind of outfit… "

21 years old, cis woman, white, heterosexual, non-PwD, no children, incomplete higher education, Student, average family income of 4 to 10 MWs, individual car as the main mode of transport, takes 20 minutes to reach the city center from her residence

“For me it's automatic now [turning on the tracking app]…of course it's one more thing you have to think about, above all, you have to think that you have to turn on the tracking app otherwise you're going to leave someone in despair. [Once I forgot to call to let my family know where I was, there were] a million messages, them thinking I died... So there's this stress in the whole family about it. Ideally, we wouldn't have to do this... ideally, I could go out and they would think 'okay, she went to work'... I went out to work, I didn't go out to do something that would risk my life, I just went out to work! Having to create all this logistics because you're going to work is just ... "

43 years old, cis woman, white, heterosexual, non-PwD, no children, postgraduate, Teacher, average family income of 4 to 10 MWs, bicycle as the main mode of transport, takes 20 minutes to get from the city center to her residence

"We learn to walk in the streets, your posture, your gaze, your step, where you are on the sidewalk, full attention, not talking on your cell phone, looking everywhere, having an attitude to walk down the street – [it's a] fake sense of security, pretending I'm safe"

43 years old, cis woman, black, heterosexual, non-PwD, with children, complete higher education, businesswoman, average family income of 10 to 20 WMs, car as the main mode of transport, takes 5 minutes to get from the city center to her residence

"I don't have this feeling that it takes my time [performing all the tactics], but I have the feeling that it takes my freedom, I stop doing some things because these tactics that I use, the tricks, they take away my freedom, it doesn't take time because usually I do it while I'm doing something else… for example, I get on the uber, I share my location… so it doesn't take my time, but it takes my freedom because if I don't do that it looks like something is going to happen, a bad thing... and sometimes it won't even happen, but I get this feeling of not being able to do what I want, [we] lose a bit of individuality"

26 years old, cis woman, white, heterosexual, non-PwD, no children, complete higher education, Engineer, average family income of 10 to 20 Mwws, individual car as the main mode of transport, takes 8 minutes to reach the city center from her residence

Author

This research was written and conducted by Laís Leão – MSc Urban Management (PUCPR)

Supported by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation through the German Chancellor Fellowship

Publication was supported by Jararaca Lab

To reference this research use:

Leão, L. R. (2022). “We are all ‘kinda’ neurotic”: Deployment of self-protection tactics as mechanisms of urban resistance on female mobility decisions. Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná, Curitiba, Brazil.